Two Men . . . And Their Trek to Mujibnagar

Syed Badrul Ahsan:

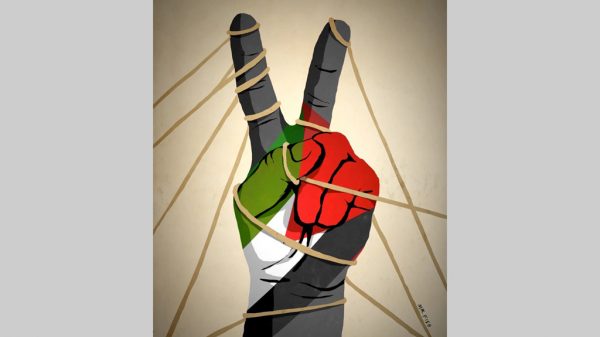

On the fearful night of 25 March 1971, two men set out on a long, tortuous trek in search of destiny. Tajuddin Ahmad and Barrister Amir-ul Islam walked through the alleys and lanes of a burning Dhaka, meshed in with thousands of other Bengalis seeking safety from the marauding Pakistan army. They made their way out of the city, hit the mud paths to the rural interior, travelled at times on rickshaws they could not always come across. And there were the times when they crossed riotous rivers on boats, sharing space with others of their countrymen, before walking on again.

Their feet were sore, their limbs were tired. Tajuddin’s feet had blisters. Both men had left their families behind and worried about their safety. They were isolated from their colleagues in the Awami League. They did not know if Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was safe or whether he had been killed by the army. Their odyssey would have included Kamal Hossain, the party’s constitutional advisor. But Hossain had parted company with them at a point in Dhaka, promising to rejoin them. He could not. Tajuddin and Amir-ul Islam would know later that Kamal Hossain had been arrested by the soldiers.

The tale of Tajuddin Ahmad and Amir-ul Islam is an inalienable and indelible part of history. As they scoured the villages, rested at humble homes on Two Men . . . And Their Trek to Mujibnagarthe way, offered encouragement to people about the future, they conversed on the requirements necessitated by the turn of events. Bangladesh’s history, they knew, called for radical change. For Tajuddin Ahmad, it was not exile that mattered, not escape from the army that was important. Paramount was the thought in him of a government that would need to take shape and disseminate its message to the world. Amir-ul Islam shared his thoughts and as the two men eventually crossed the frontier into India, they were well aware of the imperatives before them. The battle for liberation would commence, but it would be a battle shaped and strategized by a government, a government-in-exile.

Tajuddin Ahmad, ever the politician in whom the intellectual worked in frenzy, quickly made it clear to the Indian authorities that while it was necessary that Delhi come to the aid of the harassed, frightened Bengalis streaming across the border into India, it was of critical importance that he, as the second most powerful man in the now embattled Awami League, link up with the senior figures of the Indian government. In early April, he and Amir-ul Islam travelled to Delhi, where they learned that the economists Rehman Sobhan and Anisur Rahman had also arrived. Tajuddin met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who asked after Bangabandhu. It was a time when no one knew where the Father of the Nation was, but Tajuddin Ahmad informed Mrs. Gandhi that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was in touch with his colleagues and was guiding the struggle. On a later meeting with the Indian leader, he was informed by Mrs. Gandhi that Bangabandhu was in the custody of the Pakistanis and had been flown to (West) Pakistan.

The visit to Delhi spurred Tajuddin Ahmad and Amir-ul Islam into swift action. A government would have to be in place, and time was of the essence. While the Indian security and intelligence apparatus went looking for senior Awami League leaders who might have entered India, Tajuddin Ahmad recorded his speech on 10 April announcing the formation of the very first independent government in Bengali history. It was a moment reminiscent of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s act of giving shape to an Indian government-in-exile in the 1940s. It was a harkening back to the Free French government set up by Charles de Gaulle in London after France fell to the Nazis.

Tajuddin Ahmad, even as he spoke, the speech being broadcast two days later, foresaw the difficulties he would run into from his party men. Prior to the formal announcement of the government on 17 April, he and Amir-ul Islam were pelted with questions of legitimacy from unhappy Young Turks of the party, who conveyed the thought that a revolutionary council comprising the student leaders who had played a pivotal role during the non-cooperation movement in March be established to organize resistance to the Pakistan army. As other senior Awami League leaders trekked into India, exhausted after what were clearly circuitous journeys to safety, Tajuddin Ahmad and Amir-ul Islam met them as they came to West Bengal and Assam and Tripura. Tajuddin, having assumed the office of Prime Minister, spelt out every detail related to his action to Syed Nazrul Islam, AHM Quamruzzaman and M. Mansoor Ali. He soon had them on board. Khondakar Moshtaque Ahmed, who had thought his seniority in the party entitled him to the position of Prime Minister, demanded and was given the portfolio of Foreign Minister.

It was Barrister Amir-ul Islam’s strenuous responsibility to officiate as the spokesperson of the fledgling government as well as advisor to Tajuddin Ahmad. He drafted the Proclamation of Independence, which was read out at Baidyanathtola on 17 April by Professor Yusuf Ali. It was his responsibility to meet journalists, Indian as well as western, at the Calcutta Press Club and ensure their presence at the inaugural ceremony of the Mujibnagar government and then have them ferried back to Calcutta. A day after the formal inauguration of the government, on 18 April, Hossain Ali, the Bengali who was Pakistan’s Deputy High Commissioner in Calcutta, defected to Bangladesh with his staff. The offices of the Pakistan mission swiftly turned into the Bangladesh mission, with the Bangladesh flag replacing the Pakistani one atop the building.

The times were in ferment. Eleven days before the Mujibnagar government took shape, on 6 April, two brave young Bengali diplomats at Pakistan’s mission in Delhi, KM Shehabuddin and Amjadul Haq, turned their backs on Pakistan in protest against the genocide in their occupied country and declared their allegiance to Bangladesh. The future lay in the fog of uncertainty and yet these two men displayed extraordinary courage through their patriotism. Principle was at work, just as principle lay at the basis of everything Tajuddin Ahmad and Amir-ul Islam accomplished between 25 March and 17 April — and beyond.

Tajuddin Ahmad’s moral strength and political sagacity, so ably supported by Amir-ul Islam, overcame opposition to his stewardship of the government. At Siliguri, where Awami League MNAs-elect and MPAs-elect came together, ostensibly to vote Tajuddin out of office, the tables were turned by the arguments put forth by the Prime Minister and his erudite aide. From then on, it was a journey, with occasional pitfalls along the way, to liberation.

The story of Tajuddin Ahmad and Amir-ul Islam, of the travails they endured, of the long and relentless trek they made to Mujibnagar, remains an epic in the Bengali movement for self-expression, in Bengalis’ painful, blood-drenched journey to freedom.

In this month of April, fifty years on, we celebrate them, for they lit the lamp of liberty through the gathering darkness and amidst dying hope. The darkness was rolled back. Hope was kindled anew. The lamp burned increasingly bright.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a writer and columnist

Leave a Reply